Since his 2016 campaign, President Donald Trump championed an aggressive trade policy aimed at reducing trade deficits, reviving domestic manufacturing, and strengthening national economic security. His administration’s tariff initiatives—particularly targeting China, the European Union, Mexico, and Canada—were framed as necessary measures to rectify long-standing economic imbalances. This article critically examines the rationale behind Trump’s tariff initiatives by analyzing key economic indicators, including the U.S. trade deficit, national debt, industrial production growth, and corporate profits.

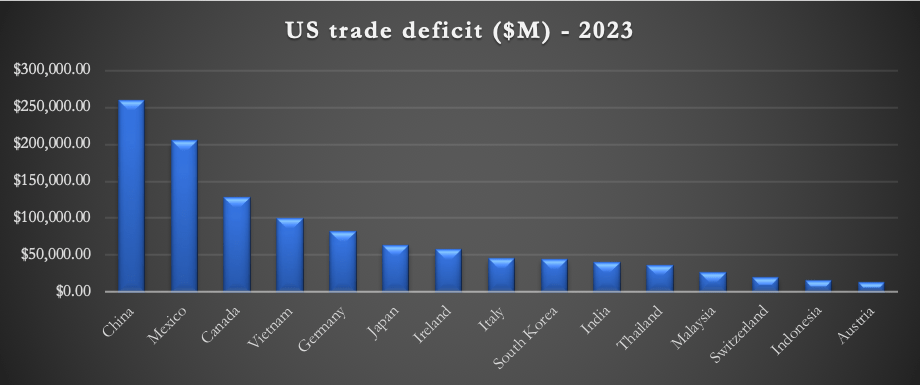

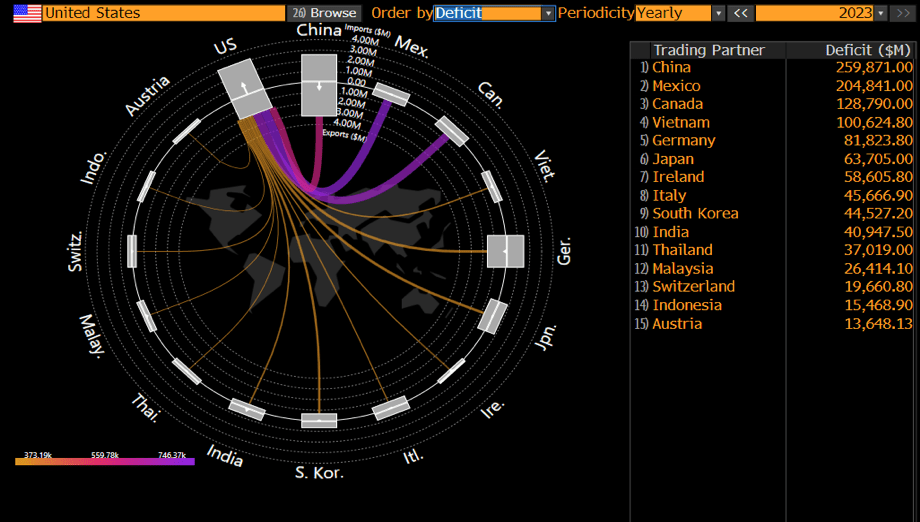

The U.S. Trade Deficit and the “America First” Trade Policy

A central justification for Trump’s tariffs was the persistent U.S. trade deficit, especially with China. The Trump administration argued that the United States was being exploited through unfair trade deals and practices by the Chinese government, including currency manipulation and subsidies, which provided a competitive edge to Chinese exports. These advantages contributed to the decline in U.S. exports relative to the rising importation of cheaper Chinese goods, showcasing a significant imbalance in trade. This situation not only affected various sectors, such as manufacturing and agriculture, but also sparked concerns about job losses for American workers who found it increasingly difficult to compete with lower-priced imports. Deficits with other U.S. trading partners, including Mexico, Canada, and the European Union, also remained high over the years, largely due to declining U.S. exports to these regions. The overall impact of these trade dynamics raised debates about the effectiveness of U.S. trade policies and the need for comprehensive reforms to ensure a fairer trading environment that could benefit American industries and workers alike.

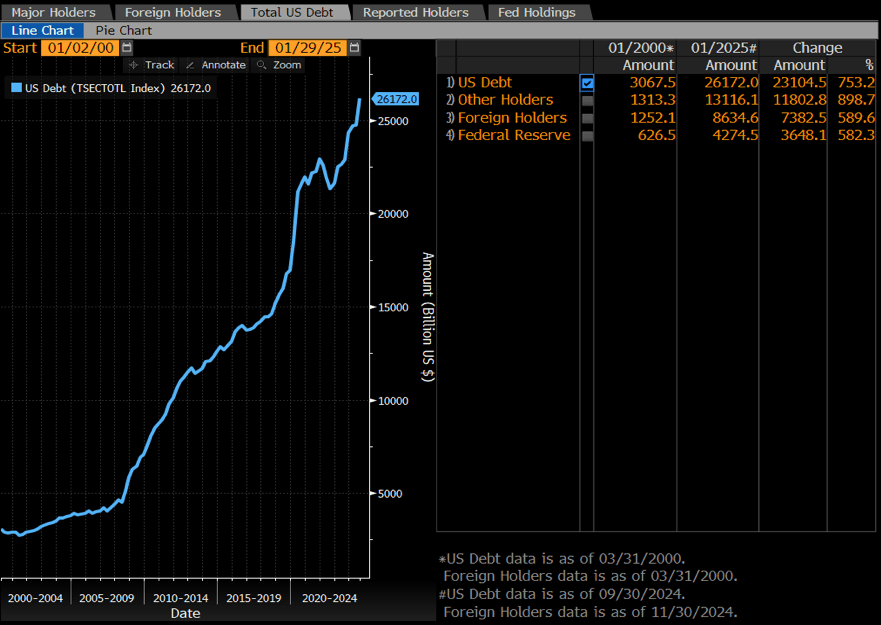

Burgeoning National Debt

Another economic backdrop to Trump’s tariff initiatives was the rising national debt, a pressing issue that has persisted for years and raised alarms among economists and policymakers alike. The current Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent, during his confirmation hearings, alluded to this concern, emphasizing the need for sustainable fiscal policies. The Trump administration has strategically positioned tariffs as revenue-generating mechanisms that could potentially offset some of the growing debt, thereby reducing dependency on foreign borrowing and enhancing domestic economic stability. This approach aimed to encourage American manufacturing and promote job creation while addressing the ever-increasing national debt. As of 2023, total U.S. debt stands at approximately $28.83 trillion, equivalent to 123% of GDP, which highlights the urgency for innovative strategies to manage and reduce the fiscal burden on future generations.

Manufacturing decline, the result of cheap imports?

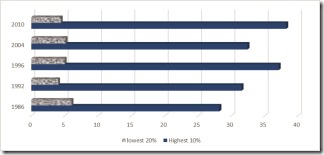

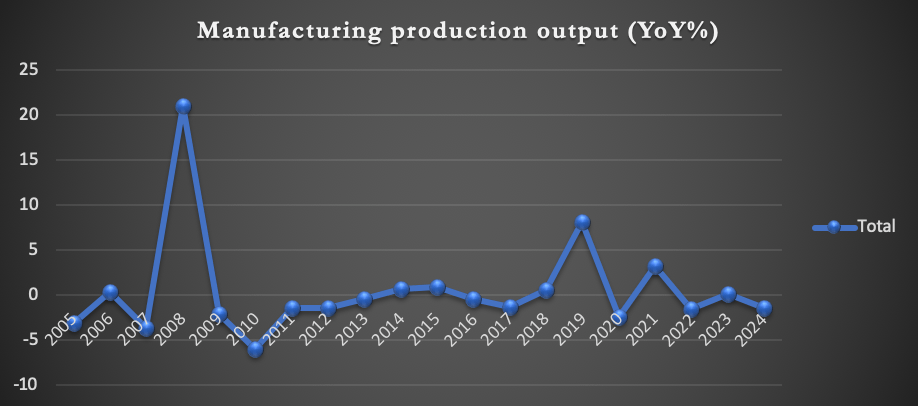

One of Trump’s strongest appeals to voters was the promise to restore American manufacturing, a sector that many perceived as vital to the nation’s economic strength and independence. His administration asserted that tariffs would shift consumption toward domestic goods and pressure companies to bring production back to the U.S., thereby reviving industrial output and creating countless jobs for American workers. This strategy aimed to not only revitalize factories but also to bolster local economies by encouraging consumer spending on homegrown products. Indeed, current figures show that average manufacturing production output growth post-COVID has stagnated, following an initial increase during Trump’s first term between 2017-2020, which raised questions about the sustainability of such initiatives and the long-term impact on American competitiveness in a global market increasingly dominated by automation and innovative technologies. As stakeholders analyze these trends, the future of American manufacturing remains a topic of intense debate and concern.

Manufacturing output initially saw a boost, particularly in industries benefiting from protectionist policies during the administration’s first term between 2018-2020, which encouraged domestic production and reduced reliance on foreign imports. However, by 2019—before the COVID-19 pandemic—manufacturing growth had stagnated, in part due to higher costs for imported raw materials such as steel and aluminium, which had seen significant price increases as global supply chains were disrupted. Additionally, the rise in energy prices, resulting from the Russia-Ukraine war, placed further strain on manufacturers already grappling with escalating operational costs. The previous administration’s ineffective energy policies contributed to this volatile energy landscape, creating an environment where businesses struggled to maintain profit margins. Collectively, these factors created a challenging climate for the manufacturing sector, which now faced the dual pressures of surging input costs and an increasingly uncertain economic outlook that hindered expansion efforts.

Corporate Profits and Industrial Production Growth

Figures on average corporate after-tax profits indicate an increase during Trump’s first term, particularly between 2020 and 2021. This upward trend can be attributed to several factors that played a significant role in shaping the economic landscape of that era. Tariffs, implemented as part of a broader trade strategy, could be credited with boosting domestic production, thereby providing a protective shield for certain industries and consequently enhancing corporate profits. While some sectors, particularly those reliant on foreign inputs, faced rising production costs due to trade policies and supply chain disruptions, others, such as steel manufacturing, temporarily benefited from reduced competition and increased demand for domestic products. This dynamic interaction between increased tariffs and domestic production led to notable shifts in profitability across various industries. Overall, growth in key industries offset declines in others, resulting in a net positive effect on corporate profits that reflected a complex economic environment. Additionally, corporate profits were bolstered by the tax cuts initiated by the Trump administration between 2017 and 2021, which aimed to stimulate investment and consumer spending; these cuts not only increased disposable income for businesses but also encouraged reinvestment into operations and workforce expansion, further contributing to the positive trend observed in corporate profitability during this time frame.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Trump’s Tariff Policy

In conclusion, the Trump administration’s tariff initiatives are driven by legitimate concerns about trade imbalances and economic security, reflecting a growing recognition of the need to protect domestic industries from unfair competition. While there were short-term gains in specific industries, such as steel and aluminum, alongside losses in others, particularly those reliant on imported goods, broader economic indicators suggest that tariffs, if applied judiciously and strategically, could contribute to a sustained manufacturing resurgence. This resurgence could stimulate job creation within the manufacturing sector, bolster local economies, and encourage innovation among domestic producers. Furthermore, a decrease in the trade deficit, achieved through a more balanced approach to trade policies, could enhance national economic stability and strengthen the United States’ position in the global market. Ultimately, the long-term effectiveness of these tariffs would depend on careful oversight and adjustments to ensure that the measures do not inadvertently harm other critical sectors of the economy.

Overall, one thing is certain: doing nothing is not a viable option if America is serious about reducing its burgeoning debt, trade deficits, and declining manufacturing output. In the current global economic landscape, where competition is fierce and markets are increasingly interconnected, it becomes crucial for the United States to adopt proactive measures. Particularly in the context of China’s ‘deliberate’ currency devaluation practices, which undermine fair competition, government subsidizations that distort market dynamics, and relatively low labour costs that make it difficult for American manufacturers to compete, protective measures such as tariffs remain a contentious but necessary tool in shaping U.S. trade policy and countering the Chinese. These tariffs not only serve to protect domestic industries and jobs but also encourage a shift towards innovation and sustainable practices, ultimately fostering a more resilient economy that can withstand future challenges. As such, a thoughtful approach to trade policies is imperative for reviving American manufacturing and ensuring long-term economic stability.